By Tamara Schaal

Note: The following reflects my experiences as part of the MULTAGRI project with finding the “right” terms to describe agri-environmental management in the federal state of Lower Saxony in Germany. This article does not take into account the latest reform of the Common Agricultural Policy resulting in a separate measure for organic farming, which had often been co-funded by the EU under measure 214 ‘agri-environment payments’ in the 2007-2013 programming period.

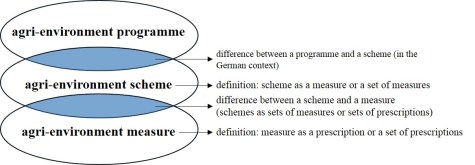

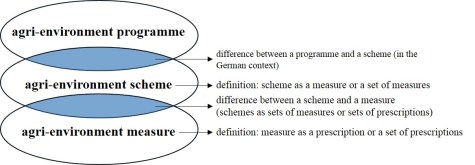

In this blog post, I consider the different words people use to describe agri-environmental management under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). As part of CAP (pillar 2), which supports the development of rural areas (EP 2015), the European Union (EU) co-funds commitments made by farmers or other land managers to provide environmental services through the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) (Council Regulation 1698/2005). Broadly, member states or regional governments develop agri-environmental programmes, which consist of agri-environment schemes, which in turn comprise agri-environment measures (EC 2005; Kleijn & Sutherland 2003). However, when comparing how these terms are used in practice the boundaries between the terms become blurry, and terms seem to be used interchangeably and variably between authors and areas. For example, some authors pertain to (the) agri-environment measure(s) when generally discussing the EU measure under which funding is provided for the agri-environment (Keenleyside et al. 2011; Uthes & Matzdorf 2013). This and other EU-funded measures aim to achieve the different goals or priorities of the rural development policy. To illustrate the inconsistencies in terminology, and to try to add some clarity, I present several examples pointing out the different use of these terms related to the agri-environment.

Agri-environment measure usually refers to the commitment made by the farmer. This might refer to specific prescriptions (Kleijn & Sutherland 2003). Examples are “a reduction in stocking densities or a cessation of fertilizer inputs” (Kleijn & Sutherland 2003: 949). Most commonly, agri-environment measures are understood as individual measures, which usually encompass several prescriptions to farmers (Degenfelder et al. 2005; EC 2005). An example from the federal state of Lower Saxony in Germany in the 2007-2013 programming period is the measure A6 ‘multi-annual flower strips’. However, Keenleyside et al. (2011) who developed a typology of entry-level agri-environment schemes, called these measures different types of management action. This shows that different terms are used to describe these voluntary commitments by farmers.

Moreover, a distinction between the terms agri-environment measure and agri-environment scheme is often absent in the literature (see for example Russi et al. 2014) and the terms are not used consistently in practice. The discussion on result-oriented approaches, whereby farmers receive payments for achieving a certain outcome (Burton & Schwarz 2013), provides an example for these differences regarding terminology. An outcome-based approach has for example been implemented in Lower Saxony (measure B2 “support of species-rich grassland sites based on a payment-by-results approach” (Groth 2010: 14)), which has been classified as a result-oriented agri-environment scheme (EC 2015) but also a result-oriented measure (Russi et al. 2014). Another example, which highlights the inconsistencies regarding terminology is organic farming. It is described as a scheme (Kleijn et al. 2006), a category of measures (EC 2005), and a measure (Degenfelder et al. 2005; Scheper et al. 2013).

Finally, it remains unclear from the literature whether there is a difference between agri-environment programmes and schemes in the German federal states. For example, the Marktentlastungs- und Kulturlandschaftsausgleich (MEKA) in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg is described both as an agri-environment programme (Matzdorf & Lorenz 2010) and an agri-environment scheme (Keenleyside et al. 2011; Troost et al. 2015). Moreover, when discussing the German context, some authors just use the terms agri-environment programme and measure (Degenfelder et al. 2005; Matzdorf & Lorenz 2010). This raises the questions whether the term scheme is applicable in the agri-environment programmes of the German federal states and if so what it pertains to.

Figure: Key areas of ambiguity of agri-environmental terminology

But how can these inconsistencies regarding terminology be explained? Several authors argue that the design of agri-environment measures and agri-environment programmes and their structure vary significantly across different countries in the EU (see for example Keenleyside et al. 2011) and in some cases even within one country (see e.g. Hartmann et al. 2006). This renders a comparison of agri-environment measures/schemes difficult and possibly also the use of the same terms.

Due to the ambiguities regarding terminology (see figure), it is challenging to know which terms to use and to consistently compare measures/schemes between different locations if the level of comparison is unclear. In my view, it is important to point out what the terms refer to in order to be able to understand differences or similarities between agri-environment programmes, schemes and measures.

In a nutshell

Terminology regarding agri-environmental management under the CAP is fuzzy as the brief overview of literature has shown and often lacking clear demarcations between the terms discussed above. Explaining what the terms agri-environment programme, scheme and measure refer to would provide clarity about the level at which comparisons are made: the level of prescriptions, single measures or sets of measures.

References

Burton, R.J., Schwarz, G. (2013) Result-oriented agri-environmental schemes in Europe and their potential for promoting behavioural change. Land Use Policy 30 (1), 628–641.

Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005 of 20 September 2005 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) [2005] OJ L277/1.

Degenfelder, L., Lösch, S., Seibert, O. (2005) Evaluation des mesures agro-environnementales: Annexe 6: Etude nationale Allemagne. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/eval/reports/measures/annex6.pdf (accessed 26 August 2015).

European Commission (EC) (2015) Maintenance of species rich grassland through results-based agri-environment schemes – Germany, various Länder. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/rbaps/fiche/maintenance-species-rich-grassland-through-results_en.htm (accessed 18 August 2015).

European Commission (EC) (2005) Agri-environment Measures: Overview on General Principles, Types of Measures, and Applications.

European Parliament (EP) (2015): Fact Sheets on the European Union. Second pillar of the CAP: rural development policy. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/atyourservice/en/displayFtu.html?ftuId=FTU_5.2.6.html (accessed 26 August 2015).

Groth, M. (2010) The use of markets for biodiversity in Germany: where are we and where should we go from here? Available from: http://www.diss.fu-berlin.de/docs/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/FUDOCS_derivate_000000001394/Groth-The_use_of_markets_for_biodiversity_in_Germany-116.pdf (accessed 24 August 2015).

Hartmann, E., Schekahn, A., Luick, R., Thomas, F. (2006) Kurzfassungen der Agrarumwelt- und Naturschutzprogramme: Darstellung und Analyse von Maßnahmen der Agrarumwelt- und Naturschutzprogramme in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. In: Bundesamt für Naturschutz (ed.): BfN-Skripten 161. Bonn.

Keenleyside, C., Allen, B., Hart, K., Menadue, H., Stefanova, V., Prazan, J., Herzon. I., Clement, T., Povellato, A., Maciejczak, M., Boatman, N. (2011) Delivering environmental benefits through entry level agri-environment schemes in the EU. Report Prepared for DG Environment, Project ENV.B.1/ETU/2010/0035. Institute for European Environmental Policy: London.

Kleijn, D., Baquero, R.A., Clough, Y. et al. (2006) Mixed biodiversity benefits of agri-environment schemes in five European countries. Ecology Letters 9(3), 243–254.

Kleijn, D. Sutherland, W.J. (2003) How effective are European agri-environment schemes in conserving and promoting biodiversity? Journal of Applied Ecology 40, 947–969.

Matzdorf, B., Lorenz, J. (2010) How cost-effective are result-oriented agri-environmental measures?—An empirical analysis in Germany. Land Use Policy 27 (2), 535–544.

Russi, D., Margue, H. & Keenleyside, C. (2014) Result-Based Agri-Environment Measures: Market-Based Instruments, Incentives or Rewards? The case of Baden-Württemberg. A case-study report prepared by IEEP with funding from the Invaluable project.

Scheper, J., Holzschuh, A., Kuussaari, M. et al. (2013) Environmental factors driving the effectiveness of European agri-environmental measures in mitigating pollinator loss – a meta-analysis. Ecology Letters 16(7), 912–920.

Troost, C., Walter, T., Berger, T. (2015) Climate, energy and environmental policies in agriculture: Simulating likely farmer responses in Southwest Germany. Land Use Policy 46, 50–64.

Uthes, S., Matzdorf, B. (2013) Studies on agri-environmental measures: a survey of the literature. Environmental Management 51(1), 251–266.