By Elisa Kochskämper

This May, the Richard Wesley Conference on Environmental Politics and Governance was convened for the first time by the Center for Environmental Politics of the University of Washington, and with the financial aid of Richard B. Wesley and Virginia Sly. This new conference set two ambitious goals: to showcase the best and most innovative scholarship on environmental politics and governance; and start to build a new research community for this research field. The need to better demarcate the field of Environmental Politics and Governance (EPG) stems, according to the conference convenors of the conference, Aseem Prakash and Peter May (University of Washington, Seattle), from a current paradox: although the importance of analyzing present environmental challenges and required solutions is widely recognized by society and academia, EPG remains an understudied area in the social sciences. They identify a ‘silo approach’ as a major reason for this, as EPG scholarship is scattered among various subfields and sub-disciplines without sharing knowledge or results and therefore without building a firm common ground.

With these aims in mind the conference was organized from the 14th to the 16th of May in Seattle. After an initial welcome session on the first evening, eight panels were distributed over the following two days. Furthermore, post-dinner conversations that reflected on the intended community-building process took place every evening. Yet, did this conference meet its aims and differ from other conferences on EPG? It did. Below I offer some reflections on the reasons.

- Small group size

A group of 45 scholars was gathered by Aseem and Peter in a small center for environmental education on Bainbridge Island, around 16km from Seattle, amidst the lush forests of Washington State. I mention the location because it was one of the factors that created the exceptional, original and inspiring atmosphere the conference transmitted during its whole course.

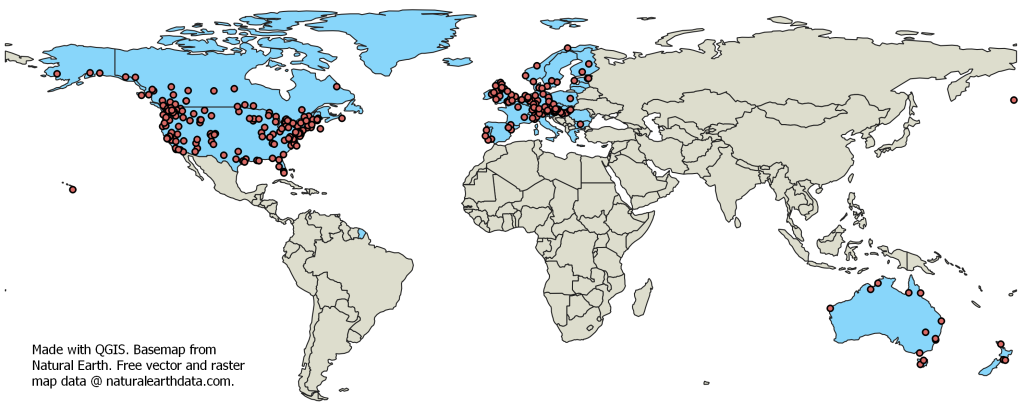

The small group size, resulting from a selection process out of 290 abstracts, involving contributions of over 400 scholars from 40 countries, was another factor. We met for breakfast, lunch and dinner, attended all paper presentations, as there were no parallel panels, and participated in all post-dinner conversations. Discussions on current or recent research projects, home university, common difficulties for publications but also on hobbies or personal backgrounds, emerged completely naturally and by the end of the second day, all participants knew each other. Professional – and personal – knowledge exchange and input was therefore high (inside and outside the panels) and extremely valuable. Whether such a small group size would be viable for future conferences was one of the more controversial discussion topics in the post-dinner conversations

- High quality of papers

A defining feature of the conference was the consistently high quality of the papers presented. 32 papers addressed topics ranging from global, national and local issues, or analyses of scale (global institutions, networks, and interactions; policy approaches and outcomes: cross-national comparisons; city-level environmental politics and governance), to behavioral aspects and conflicts of distribution (opinions, attitudes, and environmental communication; conflict and cooperation in subnational governance), to pertinent substantive environmental issues (emissions, decarbonization, and climate change; environmental inequalities; corporate environmentalism and greenwashing). Presenters hailed from many of the leading institutes and universities engaging with environmental policy and governance around the world, such as Stanford and Princeton University, University of California, Australian National University, University of Essex, ETH Zürich or the Potsdam Institute.

- Interdisciplinarity

The aim to reach out to diverse subfields of EPG and foster interdisciplinarity was also met, albeit to a lesser extent. Regarding disciplines, political science predominated, although this homogeneity was extensively discussed during the post-dinner conversations. Apart from representation of a larger diversity of disciplines from the social sciences, calls were also made to reach out more to natural scientists. For us, coming from a group with the background of geography, environmental law and political science in EDGE, it was rather surprising that papers with more than two authors, which additionally come from different fields, were difficult to find. But this, again, might be due to the strong focus on political science coming from the Anglo-Saxon context. Geographically, representation from other western countries was rather low, let alone representation of developing countries. Finally, regarding group composition and coverage of topics, we were somewhat surprised that the whole resilience and earth-system governance scholarship was not present.

- Cutting-edge methods

One effect of the aforementioned Anglo-Saxon political science bias might be the emphasis on quantitative methods – only 4 out of 32 papers worked with qualitative methods. Quantitative methods were highly sophisticated and it was in particular methodologically instructive to see experimental designs on the rise. Yet, the low representation of qualitative approaches and absence of mixed methods seemed to undermine to a certain degree the intention to bring one research field comprehensively together and achieve sound theoretical insights. This, however, was also mentioned in one evening discussion session.

- Outlook

Nonetheless, these were rather formal or organizational points, which seem to be quite normal for a first conference, which is intended to mark a starting point for the gradual definition of a potential new or stronger field. The conference is planned to continue in a rotating, self-organizing manner, and the next conference is set to be held in Gerzensee, Switzerland, so many of the points raised above can be easily addressed already in the second Richard Wesley Conference on Environmental Politics and Governance. In case you are now more interested in the conference and emerging research community, you can sign up to the listserver, which was set up to provide information on, and facilitate knowledge sharing within the research community. Abstracts for the second conference are due soon, by November 3, 2015; do not miss the opportunity, we are still amazed by our outstanding stay on Bainbridge Island.

See our presentation in EDGE – Presentations.