Three Types of Institutional Innovations Show How to Represent Future Generations in Political Decision-Making Today

By Michael Rose

The choices we make in politics today, whether regarding biodiversity loss, climate change, or social security systems, hold significant repercussions for the well-being of future (i.e., yet unborn) generations. The fact that future generations have no voice today may contribute to the governance failures prevalent in these realms and others. From a democratic perspective, the interests of all affected by political decisions should be considered in their formulation. Moreover, the guiding principle of sustainable development asks us to consider the needs of future generations alongside those of the present. But how could we give a voice to people who do not yet exist?

Several democracies have responded to this challenge by establishing specialized institutions. For instance, in 1993, the Finnish Parliament formed the Committee for the Future. Shortly thereafter, in 1995, Canada established the Commissioner for Environment and Sustainable Development. Both institutions remain active today. From 2001 to 2005, the Israeli Knesset had a Parliamentary Commissioner for Future Generations. Following suit, in 2008, the Hungarian Parliament introduced an Ombudsman for Future Generations, although this position was later downgraded by the Orbán Government in 2012. Notably, the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales stands out as a prominent example of how democracies evolve their institutional frameworks to consider future generations today.

Twenty-five institutions in 17 democracies

In my article “Institutional Proxy Representatives of Future Generations: A Comparative Analysis of Types and Design Features”, I formulated the notion of institutional proxy representation of future generations to provide a theoretical foundation for these institutional advancements. Furthermore, I applied this concept to build a comprehensive inventory of empirical instances of institutional proxy representation across democracies worldwide. Through this analysis, I identified 25 institutions for future generations – or “proxies” – in 17 democracies.

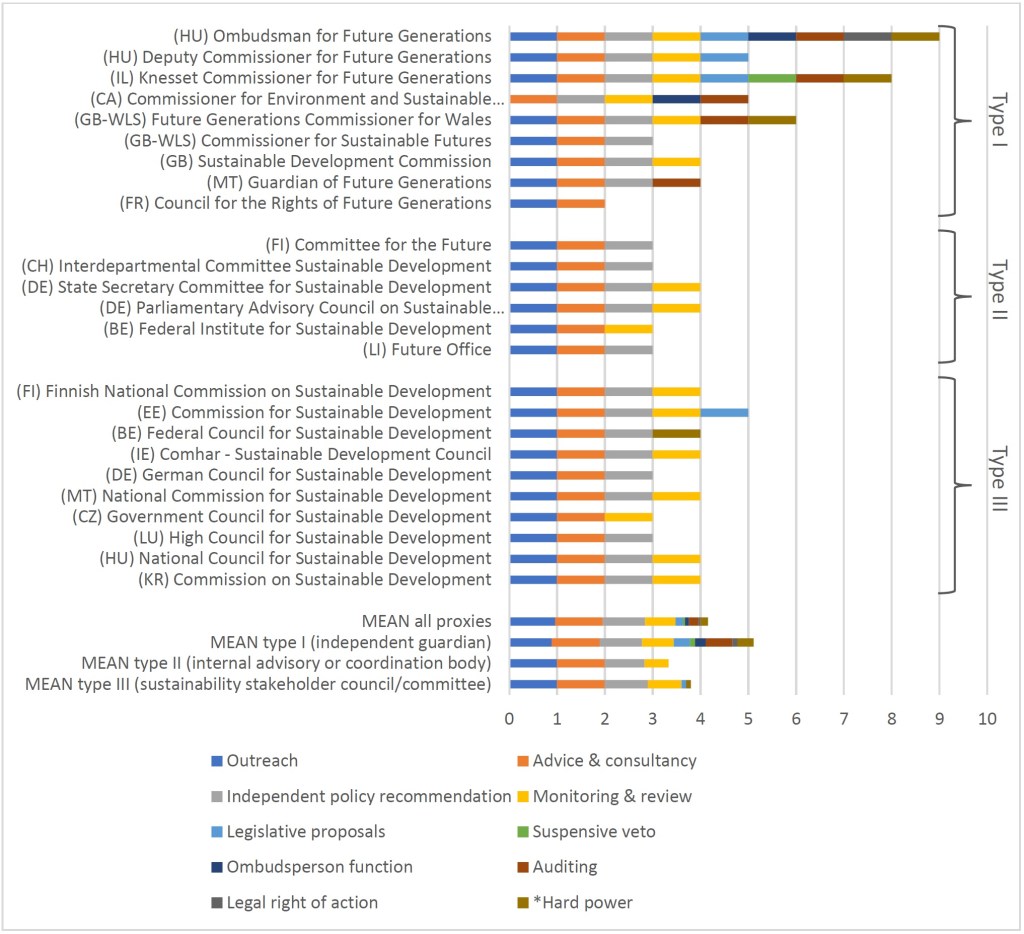

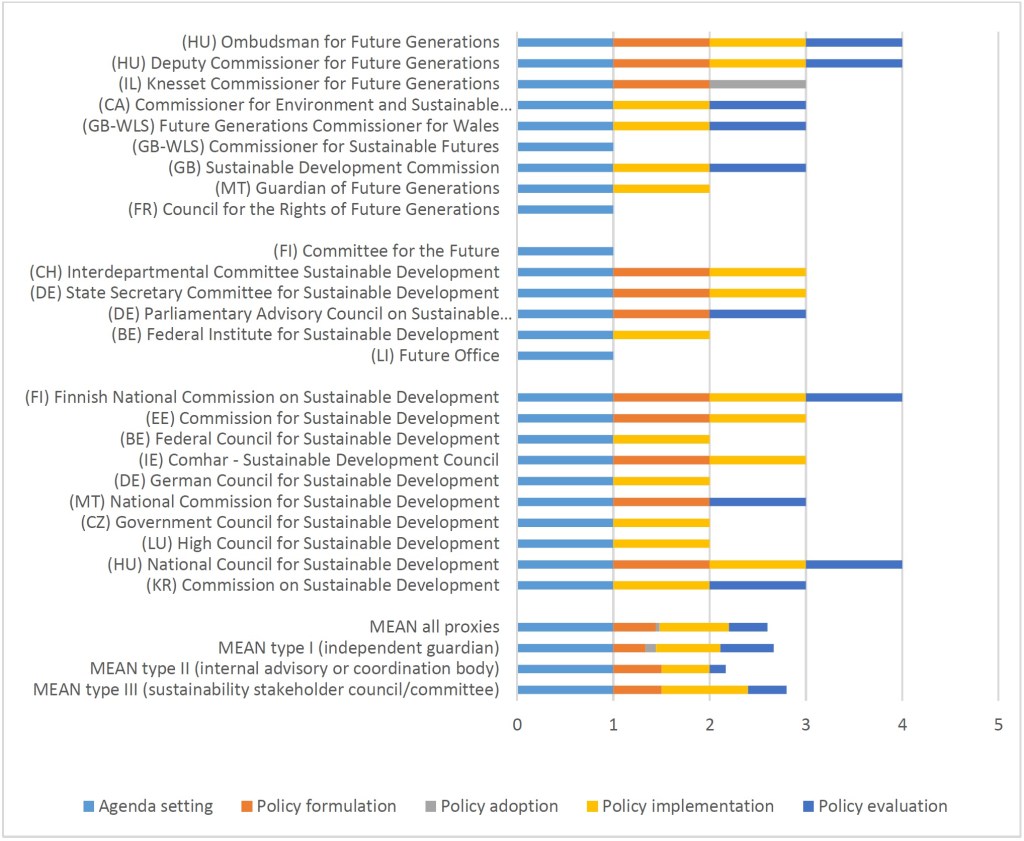

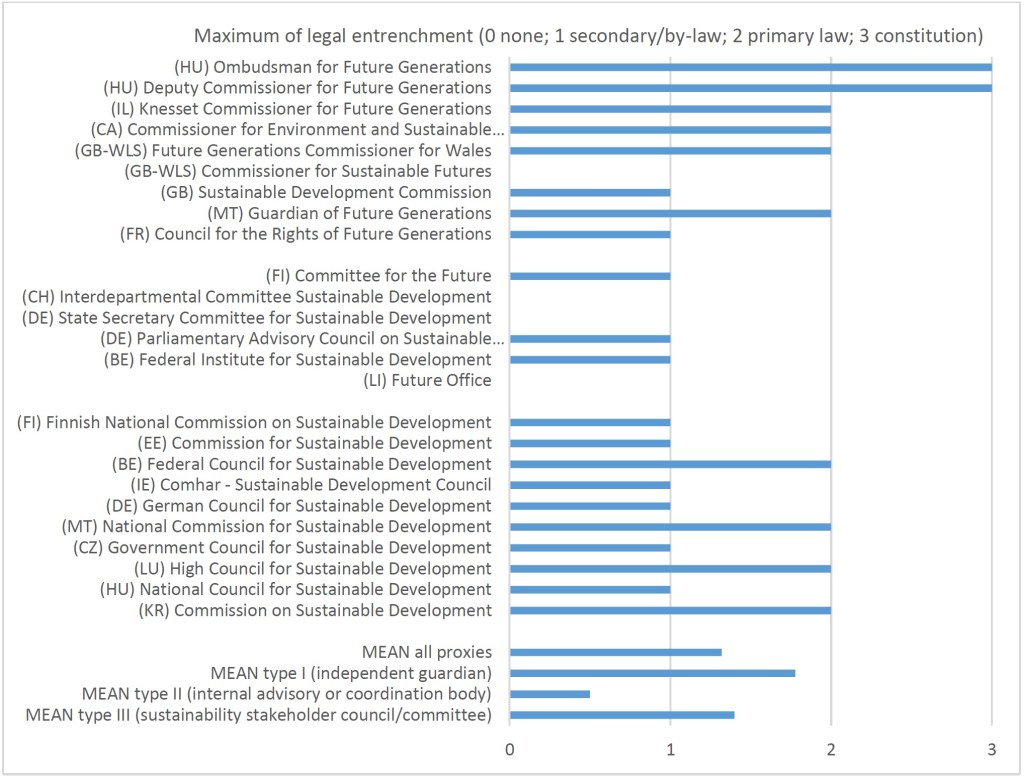

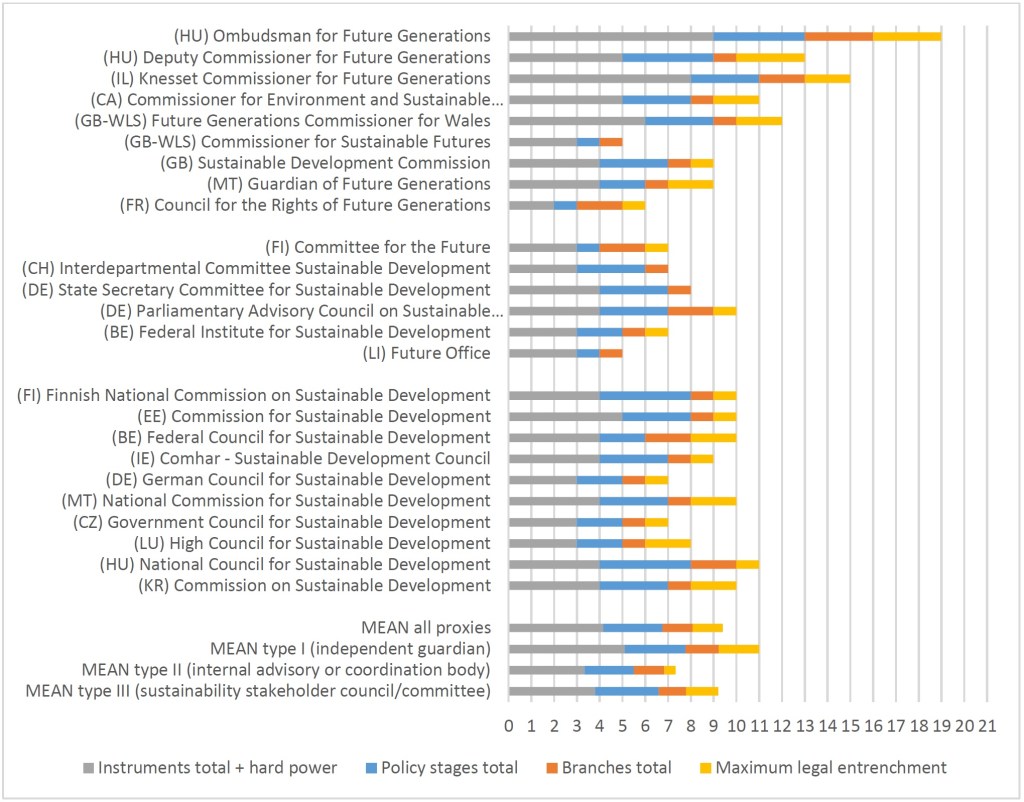

The proxies are grouped into three types, based on the rationale of selecting their members: The expertise-driven independent guardian (type I), the political or administrative advisory or coordination body (type II), and the sustainability stakeholder council or commission (type III). For each proxy (and proxy type), I assessed how it is designed, and how this translates into its formal capacity to influence political decision-making.

Three types

Type I proxies – the independent guardians – typically comprise experts who are not part of government or parliament. This allows them to consider the needs of future generations from a professional point of view with minimal political interference. These proxies often have robust legal foundations and wield specific political instruments usually not found in other proxy types, such, legal rights of action, a suspensive veto, ombudsperson functions, legislative proposals, and auditing, including independent investigation rights. Type I includes all the strongest, but also some of the weakest proxies examined in this study. The strongest ones can not only voice the interests of future generations, but can also make sure they are heard by parliament or government. However, the survival rate of type I proxies is rather low.

Type II proxies – the political or administrative advisory or coordination bodies – are, to a certain extent, the counter-model to type I. They are not independent, but internal parts of the political system, comprising either Members of Parliament or members of the governmental departments. Operating on a predominantly weak legal footing, they provide internal advisory, coordination, and sometimes monitoring services to enhance political decision-making from within, with a view toward benefitting future generations. They only have limited political instruments at their disposal and can access only few stages of the policy cycle, which makes them heavily reliant on good working relationships with other parts of parliament and government.

Type III proxies – the sustainability stakeholder councils or committees – are designated parts of the sustainability governance architecture of their host countries. Embracing the principles of functional representation and participation, members are appointed from different sectors of society to broaden societal outreach, provide general advice and specific policy recommendations to the government, and oftentimes monitor and review sustainability-related developments. While they lack particularly strong or weak formal capacities to influence political decision-making, they show the highest survival rate among the three types, possibly attributable to their integration across multiple sectors.

Design features

I assessed each proxy to determine the legal basis upon which it was established, the political instruments it was granted, and the branches of government and stages of the policy cycle it could engage with through these instruments. This figure shows the distribution of political instruments across proxies and types. Proxies were created with these instruments to allow them to monitor and influence political decision-making and reach out to society. To learn more about proxies’ access to branches of government and phases of the policy cycle, as well as their legal bases and total formal capacity to influence political decision-making, please scroll through the slideshow.

Political instruments | Access to stages of the policy cycle | Access to branches of government | Legal basis | Total formal capacity to influence political decision-making

A multifaceted landscape of institutionalized voices of future generations

In general, the diverse and dynamic array of proxies, although relatively small in number, provides manifold examples of institutional innovations illustrating how the interests of future generations can be considered in political decision-making. However, while some of these proxies can act as watchdogs with teeth when ignored, many seem to represent rather cosmetic than far-reaching reforms of the democratic decision-making process. Therefore, it is important not to place excessive expectations on these proxies in terms of effecting significant policy changes to the benefit of future generations. For more detailed and inspirational results, download the full study here.

Reference

Rose, Michael (2024): Institutional Proxy Representatives of Future Generations: A Comparative Analysis of Types and Design Features, in: Politics and Governance 12, Art. 7746 (21 pages). DOI: 10.17645/pag.7745